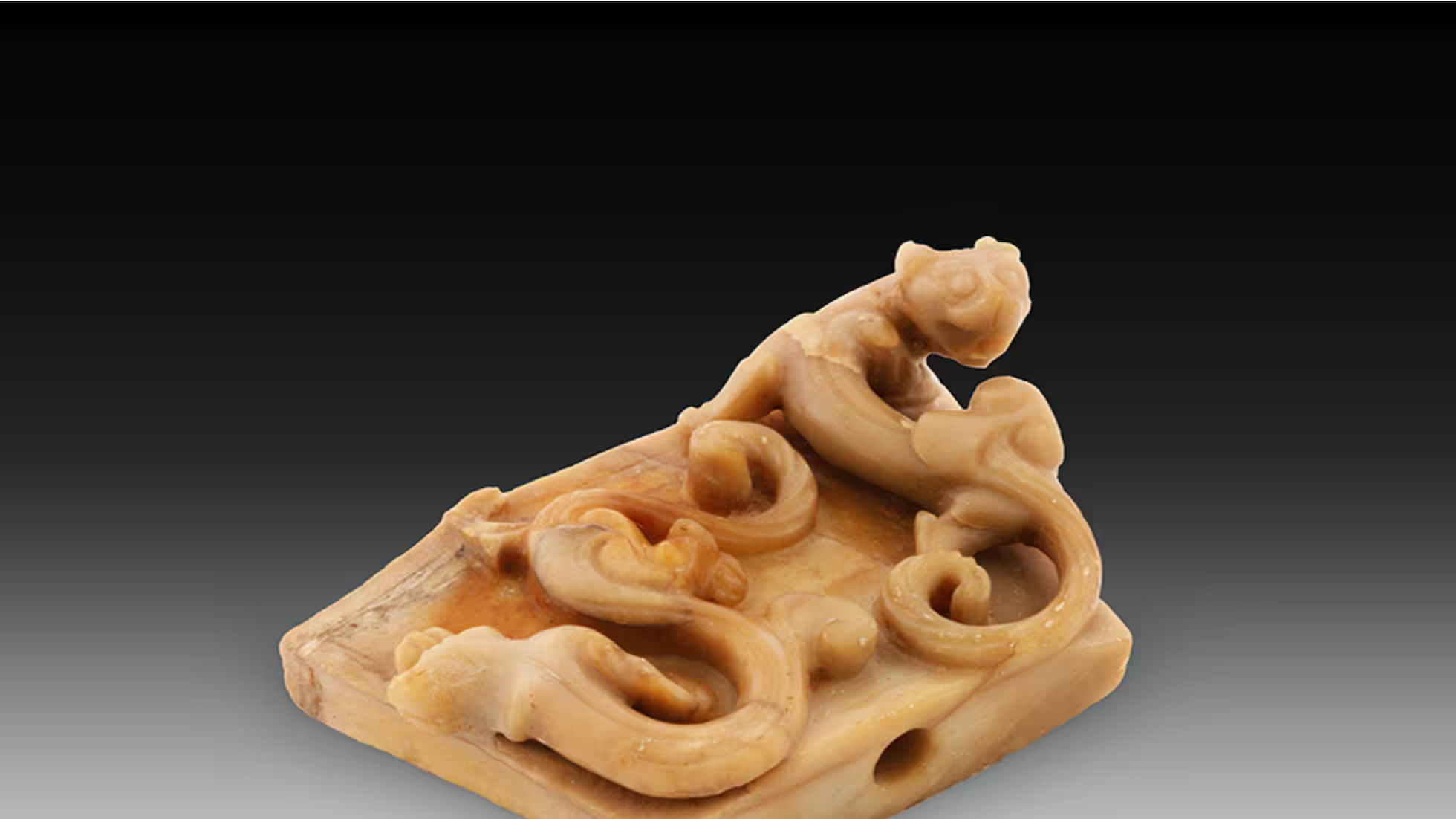

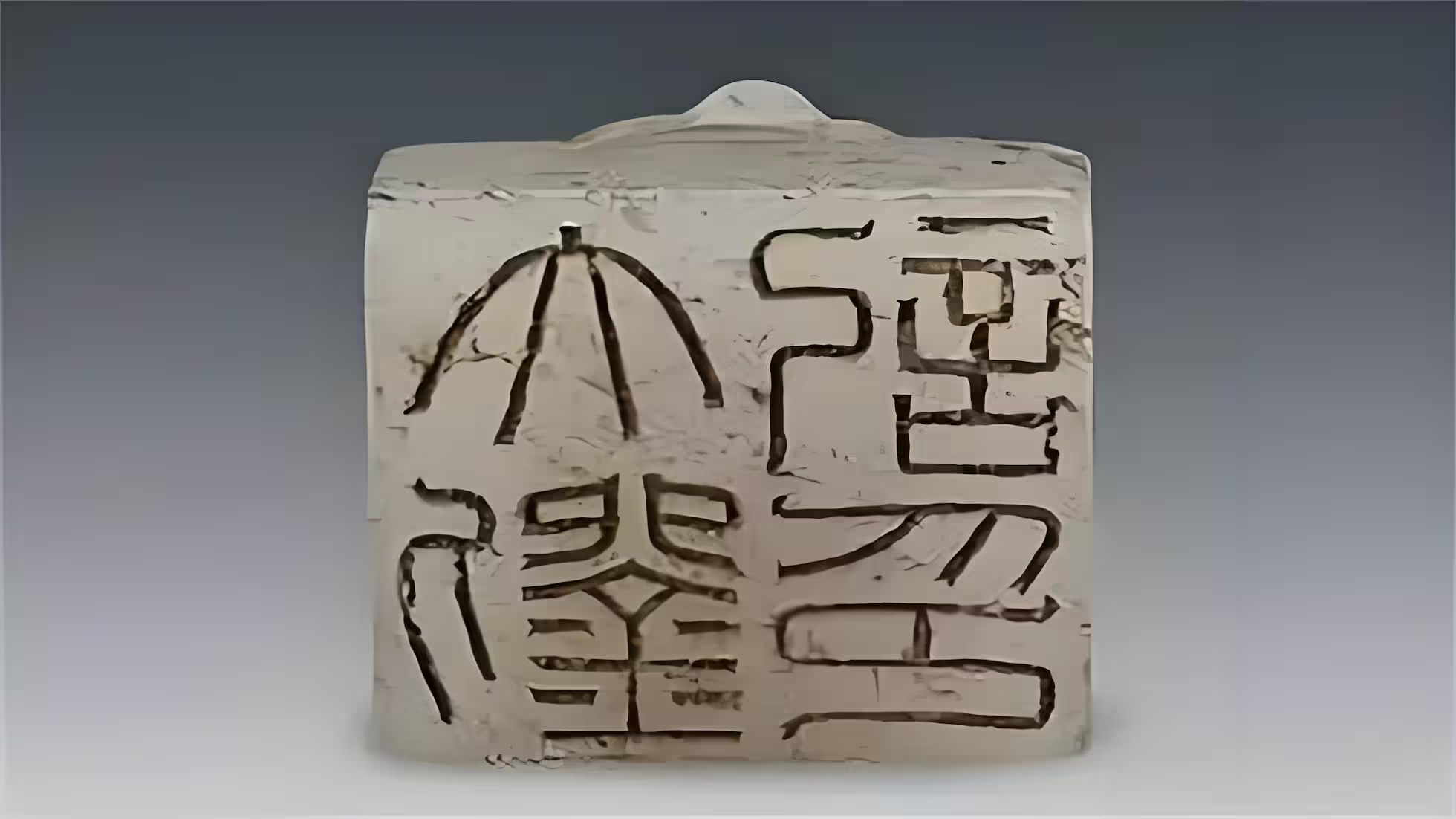

The 'Da Liu' Inscribed Seal

Han Guan Jiu Yi records: “Before Qin, the people all wore ribbons with seals made of gold, jade, silver, bronze, rhino horn, and ivory; they were square inch seals, each wearing what they preferred. Since the Qin, only the Son of Heaven called the seal a ‘xi’ and used jade; the ministers did not dare to use it.” It also says: “Princes (zhuhou wang) used golden seals with camel knobs, with the inscription ‘xi’.” “The Crown Prince used a golden seal with a turtle knob, the inscription reading ‘zhang’.” “Marquises (che hou) used golden seals with purple ribbons.”

Liu He, the Marquis of Haihun, belonged to the rank of che hou. Therefore he should have had a golden seal with a turtle knob and should not have had a jade seal. According to “Han Guan Jiu Yi,” the Son of Heaven and princes used ‘xi’, while officials ranked 600 to 200 shi used ‘yin’ of bronze with a nose-shaped knob. From this it can be known that the “Da Liu Ji Yin” is a seal that violates the regulations. Liu He was a marquis; first, he should not have used jade, and second, he should not have had a turtle knob, while “yin” was the generic name for seals of officials from 600 to 200 shi. Thus, this seal bears markings of both imperial status and that of an ordinary official, perhaps pointing to the Marquis of Haihun’s special status and circumstances, and possibly reflecting the mentality at the time the seal was made. “Da Liu Yin,” i.e., “Great Han Record Seal,” reflects the special nature of Liu He’s identity.

In the Han dynasty, when a prince or marquis died or on the day of burial, the court would dispatch officials to offer condolences, which in practice meant supervising whether the funeral violated regulations. The Later Han Book, “Rites, Part II,” states: “When princes, marquises, first-ranking consorts, and princesses pass away, they are granted seals and jade cases with silver threads (burial garments); for great consorts and elder princesses, copper threads. Princes, consorts, princesses, dukes, generals, and special counselors are all bestowed ritual vessels, twenty-four items from the imperial stores. An envoy manages the funeral arrangements and the construction. Cypress coffins are used; all officials attend the send-off, as per precedent. Princes, tutors, chancellors, commandants, and prefects oversee the funeral; the Grand Herald proposes a posthumous title; the imperial envoy bestows jade and silk; the date is set and the title granted as per ritual. After interment, officials remove coarse mourning clothes according to the code, while the family observes rites.”

Although by his death the Marquis of Haihun had already been reduced from three thousand households to only one thousand, an envoy would still be sent for supervision. Whether these two 1.75-centimeter-square seals inscribed “Da Liu Ji Yin” were seals bestowed by Emperor Xuan of Han, or noncompliant items privately interred, remains worth investigating. Another seal engraved with the two characters “Liu He” is also a nonconforming piece. It should have been a private seal carved after Liu He was deposed and returned to his native state of Changyi. Having lost all rank and under supervision as a special-status resident, he should have used materials like bronze, iron, stone, or wood to carve a seal. Yet in such circumstances Liu He dared to carve a jade seal, which may have been a special exception approved by Emperor Xuan of Han—namely, a seal bestowed after death that carried only his name without an office. Though a commoner, it still denoted nobility. Taken together—“Da Liu jade seal,” the name “Liu He,” and the “jade” material—this suggests the tomb owner Liu He’s lingering attachment to the imperial throne, or perhaps Emperor Xuan’s recognition that Liu He had once been the emperor of the Great Han.

Published at: Sep 9, 2025 · Modified at: Sep 10, 2025