The Marquis of Haihun’s Secrets to Amassing Wealth

The tomb of the Marquis of Haihun yielded 478 gold objects with a total weight of 115 kilograms, setting a record for gold artifacts unearthed from an ancient Chinese tomb. Among them were 48 horseshoe-shaped gold ingots (ma-ti jin), 25 “linzhi” gold pieces, 20 gold plates, and 285 gold cakes. By comparison, the Western Han tomb with the most gold previously found—King Liu Kuan of Jibei—contained only 4.266 kilograms; next was King Liu Xiu of Zhongshan (3.384 kg), followed by King Liu Sheng of Zhongshan (1.16 kg). These three tomb owners were all kings during the Western Han, yet the total gold from all three tombs combined is under 8 kilograms—vastly less than what was found in Liu He’s tomb.

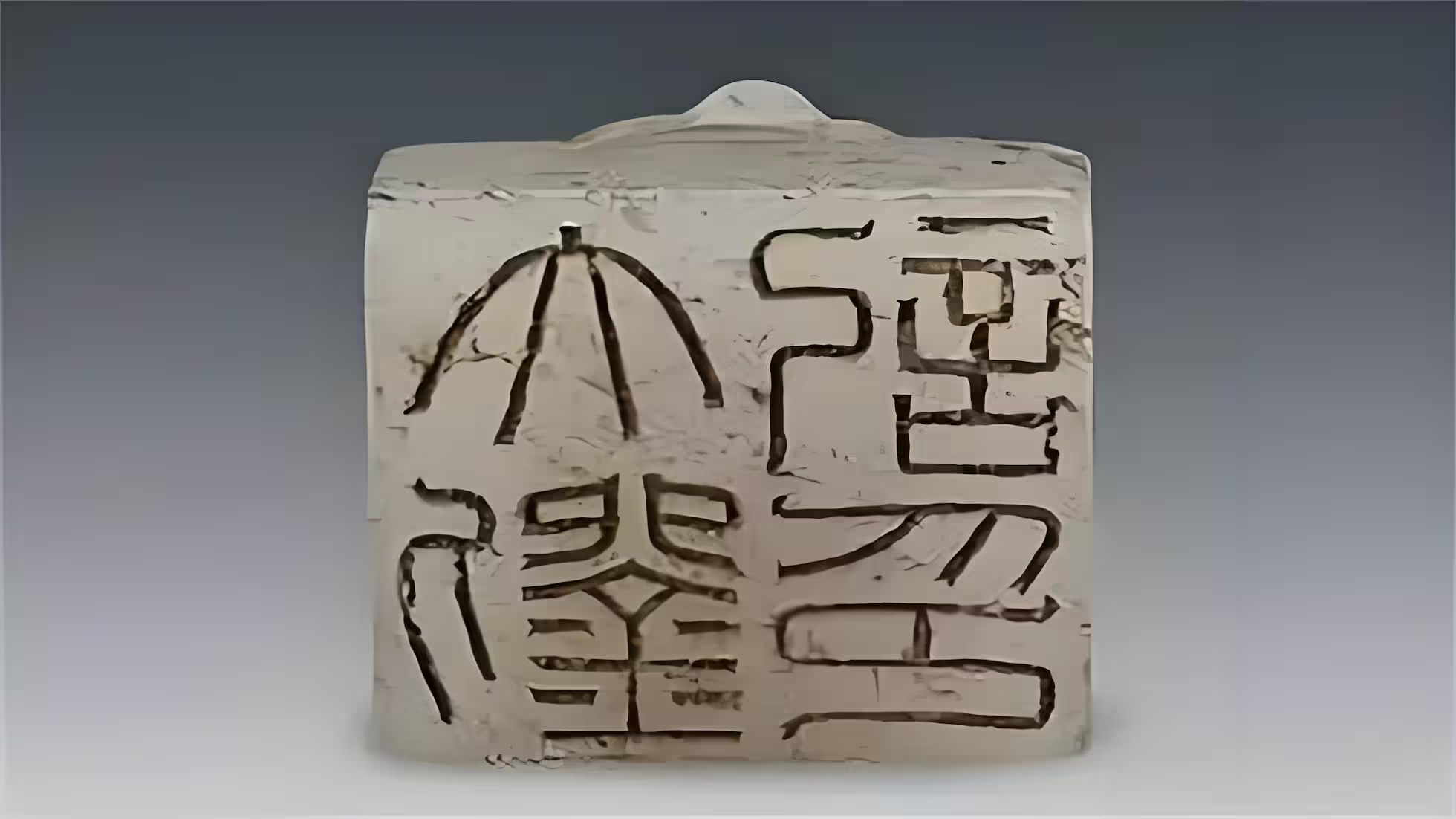

At today’s gold prices, the gold alone from Liu He’s tomb would be worth over 32 million RMB. Roughly two million bronze coins were also found—over ten tons by weight—approximately 1% of the state’s mintage that year. More than 3,000 bronze and iron objects (or sets) were excavated, including daily utensils, musical instruments, chariot and horse fittings, weapons, seals, and bronze mirrors. Everyday objects include a distillation set, steaming and boiling vessels, kettles, tripods (ding), jars (fou), handled zun and you, a wild-goose-and-fish lamp, Boshan (Bo Mountain) censers, lamps, candlesticks, a water clock (dripping clepsydra), sets of bianzhong (two stands; one set of 14 chime bells), a set of bianqing (stone chimes, here in iron), seat weights, and more.

Notably, a chapter titled “Knowing the Way” from the Analects (Lunyu Zhidao Pian) was discovered in the tomb, which strongly suggests this may be the long-lost Qi Analects. If verified, it would be a discovery of immense global scholarly significance—an artifact truly beyond price.

Based on expert appraisals, the market value of the gold artifacts alone from Liu He’s tomb far exceeds 1 billion RMB. A consistent theme across every stage of Liu He’s life—including his period as a commoner—is that he was never short of money. Considering his background and life experience, his wealth derived from several sources:

Personal accumulation This includes wealth amassed while he served as a king, an emperor, a commoner, and later as the Marquis of Haihun. Most substantial was the 14-year accumulation during his time as King of Changyi; the 10 years as a commoner and 4 years as marquis also contributed significantly. His tenure as emperor was too brief for him to take much away from the throne.

Father’s inheritance When Liu Bo (his father) died, Liu He was only five. Although lavish burials were fashionable in the Western Han, Liu Bo did not bury everything with him as many princes did; instead, he left his most valuable possessions to his only son. As a favored son of Emperor Wu of Han, Liu Bo received numerous imperial gifts—especially horseshoe-shaped gold ingots, “linzhi” gold, and gold cakes. Historical records note that Emperor Wu bestowed gifts without restraint: for example, after General Wei Qing defeated the Xiongnu, he received more than 200,000 jin of gold (one Han jin ≈ 250 g). Under Emperor Xuan, records mention 7,000 jin to Huo Guang, 5,000 jin to the King of Guangling, and 100 jin to each of 15 feudal kings. As Emperor Wu’s beloved son, Liu Bo surely received no small amount during his lifetime.

In Liu He’s native Changyi (in today’s Shandong), there are two large tombs. One is a grand rock-cut tomb at Jinshan that Liu He began for himself while he was the King of Changyi; it carved massive chambers into a cliff and must have cost a fortune. That tomb was never completed; he was summoned to the capital to be emperor and no longer needed it; later, after being deposed to commoner status, he could not use it; and upon becoming Marquis of Haihun, he died in office and was buried locally rather than returning home. Thus, his planned tomb in Changyi became an abandoned mound. Across the mountain stood another large tomb, on the earthen Hongshan, belonging to his father, Liu Bo. Excavated in the 1970s and never looted, it contained over two thousand jade, bronze, and pottery items for daily use—yet not a single gold piece or precious treasure. The more valuable items had been left to the young Liu He. After Liu He was deposed, the court even permitted that all property of the state of Changyi be granted to him.

Gifts from the previous generation Liu He’s grand-uncle (through his mother’s side) was Li Guangli, who once supported making Liu Bo crown prince. Li Guangli was the brother of the famed and favored Consort Li of Emperor Wu. He was later titled General Ershi and led the campaign to capture Dayuan in the Western Regions, bringing back the prized Ferghana “blood-sweating” horses. This delighted Emperor Wu, who ordered the minting of gold pieces cast in the shape of horses’ hooves as court rewards. For his military merits, Li Guangli received especially many horseshoe gold ingots. Because he sought to promote Liu Bo as heir, Li Guangli made substantial “relationship investments” and family gifts—undoubtedly including horseshoe and linzhi gold, symbols of honor and status. Liu Bo did not take these with him to the grave; after his death, they became Liu He’s property. This helps explain why so many horseshoe and linzhi gold pieces were found in Liu He’s tomb.

Funerary contributions from the court and relatives In the Western Han there was a system of condolence gifts (fuzeng). When a prince or marquis died, the court provided coin as a contribution, and family and friends also gave money. The tomb contained as many as two million Wu Zhu coins, weighing more than ten tons—likely the contributions from Emperor Xuan and from Liu He’s relatives and friends upon his death.

Cast and crafted during his marquisate The famous wild-goose-and-fish lamp in Liu He’s tomb likely originated from a scene he witnessed by Lake Pengli (modern Poyang Lake): a wild goose catching a fish. It stirred his feelings about destiny—he felt he was that fish clenched in the goose’s beak, unable to move. Whether as king, emperor, commoner, or marquis, he could not fully determine his own fate. Out of this sentiment came the design for the wild-goose-and-fish lamp.

Published at: Sep 9, 2025 · Modified at: Sep 10, 2025